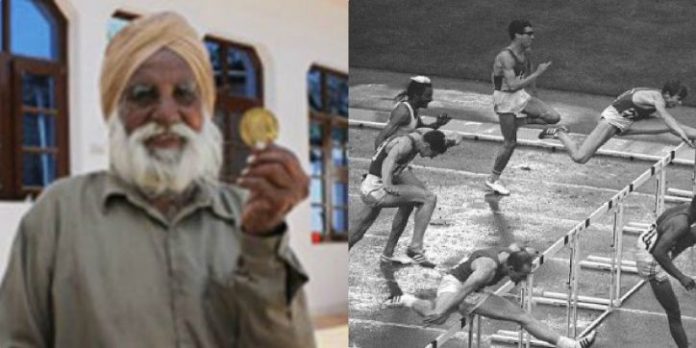

Punjab: Sarwan Singh represented India in the 110-meter hurdles in Asian Games in 1954. Life had played a cruel joke on Singh, who had gone from being a proud athlete who jumped over his hurdles on the track easily to a taxi driver who was unable to even soar above his life’s hurdles.

Back in 1954, it was his first opportunity to attend an international event. He was about to run in front of a crowd of about a lakh shouting supporters for the first time. But all he cared about were the ten obstacles in his road to his only dream: gold for his country.

He didn’t run; he sailed over the obstacles. He characterized the 14.7 seconds that took him to traverse the 110 meters as the best moment of his life. His most valuable possession was a gold medal, which he wore around his neck. He couldn’t have been more pleased with himself. And the moment he saw the tricolor rise, he remembered feeling like a military hero.

But fate had something else in mind for him. The gold medal, which was supposed to help him make a living, turned out to be worthless to the authorities. He couldn’t even get a government job with the medal. He had no choice but to beg for his life. Nobody cared about his circumstances, and his plight failed to sway anybody in authority; no one cared enough to help an Asian Games gold medallist live a dignified life.

When he retired from the Bengal Engineering Group in 1970, he faced difficult times. With no option left, Singh rented a cab from one of his buddies to support the family. He worked as a taxi driver for two decades, far from his hometown and away from his family and friends.

The Asian gold winner was handed a monthly pension of 1,500 rupees in a country where some players earn lakhs. He was obliged to till someone’s farm at the age of 70, at a point in his life when he couldn’t even walk properly, to make ends meet.

The medal-winning at Asian stage was the finest moment of his life, a moment he dearly remembered and desired he could relive. However, due to his poor financial circumstances, he was compelled to sell his prized possession, his gold. He’ll be in his 90s now, and he’s largely forgotten by the country he once made proud on the world stage.

Often people whine about our athletes’ failure to win Olympic gold, but when there are dozens of such Singhs in every part of the country, it’s an irony that no one counts on them and takes it seriously.